Let’s talk about investing for your future. One of those things you know you should be doing, but probably aren’t.

Or if you are, then probably you aren’t saving enough.

When you live your entire life in the same country, working as an employee the whole time, retirement savings are easy. Or at least easier.

You pay taxes, part of which will probably give you some sort of a government pension when you reach 65 75 or so years old.

You might even automatically save part of your monthly paycheck into tax incentivized private pension schemes. If you’re lucky, your employer might even contribute some.

Contents ↺

Probably you buy the house or apartment where you live. Then you pay down the mortgage, little by little, until it’s hopefully yours by the time you retire. That’s also a form of retirement savings.

As a nomad or serial expat, all or most of the assumptions above go out the window.

You’re much more likely to be self-employed or to run your own business. And you might be organizing how you live your life to pay very little tax. Even if you work as an employee in a given country for a while, you probably won’t stay there for long enough to qualify for a meaningful pension.

The type of savings one country will reward with tax incentives, might be penalized by the next country you choose to call home.

And since you probably prefer jumping from Airbnb to Airbnb or other short term leases, you are less likely to buy the apartment you live in. An apartment, after all, will tie you down. And who wants that?

In short, you will likely save less—unless you actively do something about your savings strategy.

In this article I will outline my simple investment strategy for global nomads and serial expats.

Read on to avoid the nomadic pension trap, and instead retire comfortably decades earlier than your non-nomadic wage slaving peers.

First, a summary for those of you who are too lazy to even skim the article:

TLDR; (too long, didn’t read;)

- Start saving/investing today.

- Aim for at least 20-60% of your income, depending on when and where you want to (be able to) retire.

- Avoid savings accounts with low interest rates.

- Invest primarily in a diversified mix of equities (stocks) and bonds, ideally through low-cost index funds or ETFs.

- Increase the proportion of bonds in your portfolio as you near retirement age.

- Buy and hold, don’t try to time the markets.

- Automate as much as possible. Avoid paying attention to the markets. Re-balance your portfolio annually.

- Live well below your means and optimize your taxes and other significant expenditures.

Why you should start saving today

The best time to start investing was yesterday. The second best time is today.

The biggest reason to start saving today is compound interest—the interest on the interest your investment already earned. The longer you hold your investments, the more powerful the effect of compound interest is.

To demonstrate the power of compound interest, let’s look at a few simple examples.

Note: Because this is such an important concept I am listing quite a few examples here. Once you’re convinced that you need to start saving ASAP, feel free to skip to the next section.

Example 1

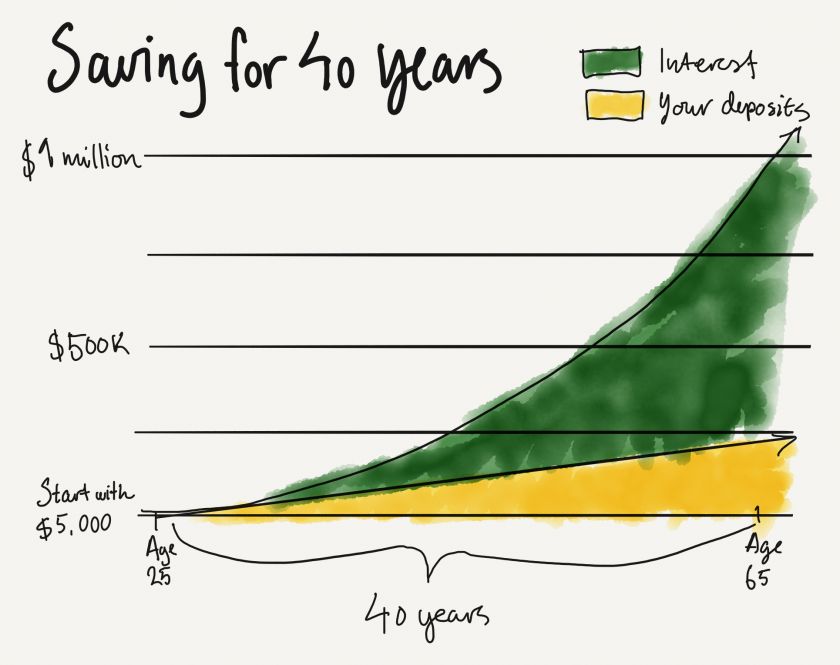

Imagine you save a modest $5,000 per year, starting at age 25 and ending at age 65.

Let’s assume that you place the savings in the stock market, and that you get average returns of about 7% (the historical average of the S&P 500 index).

40 years later, at age 65, you can retire with about $1 million in the bank, even though you have only put aside $200,000 over the years.

As you invest longer, and longer, your savings grow exponentially.

Pretty sweet, eh?

Regular savings + compound interest + lots of time = $$$

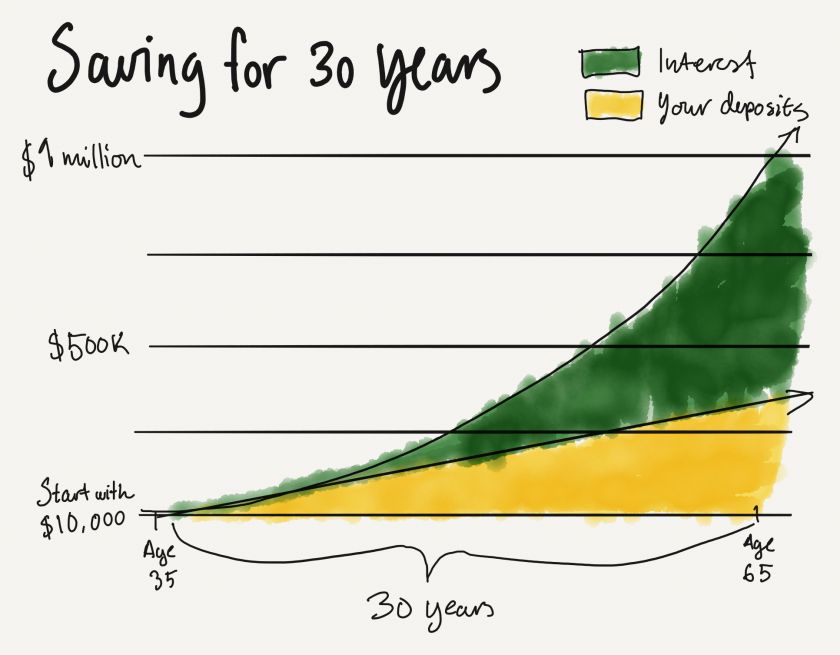

But say you start to save a decade later, yet you still want to reach $1 million by retirement. How much more do you think you need to save every year to reach your goal?

25% more? Nope.

33% more? After all, 40 years is 33% more than the 30 years you now have to save.

Still nope. Remember the effect of the compounding.

By starting 10 years later, you need to save 100% more per year (i.e. double) to reach the same $1 million at retirement.

Still good, but your money only had time to grow about half as much as if you started a decade earlier.

Need another example?

Example 2

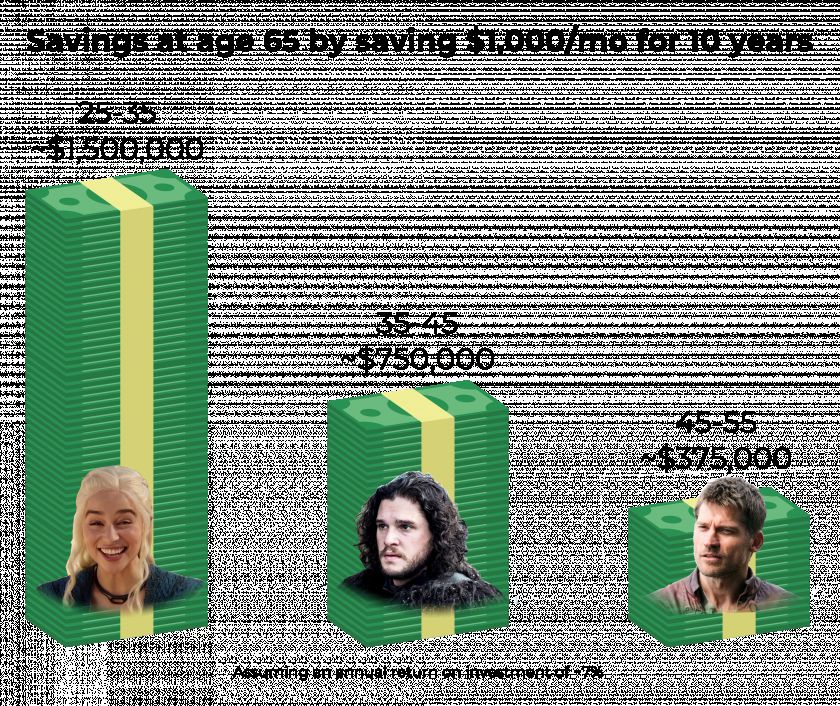

Let’s look at the fictional investments of three fictional people you may know. Each invest $1,000 monthly for 10 years, then they stop. The only difference is at what age they started to invest.

Assume they still want to retire at age 65 and get the same average annual return of 7% on their investments.

-

Daenerys starts investing $1,000 every month when she is 25 years old, then stop 10 years later at 35.

-

Jon starts investing $1,000 every month when he is 35 years old, then stop 10 years later at 45.

-

Jamie starts investing $1,000 every month when he is 45 years old, then stop 10 years later at 55.

At age 65 Daenerys will have nearly $1,500,000, Jon close to $750,000, and Jamie about $375,000.

Still need more convincing?

Example 3

What if you don’t stop saving after ten years, but keep saving until retirement? The effect will be even greater…

If you start saving $1,000 per month at age 25, and earn a return on investment of 7% per year, you will retire with $2,563,000 in the bank at age 65.

If you start saving the same amount ($1,000/mo) at age 35, earning the same return, you will retire with about $1,212,000 in the bank at age 65.

If you start with the same savings plan at 45, you’ll retire with about $526,000 in the bank at 65.

If you only start saving at 55, you’ll have a meager $177,000 in the bank by retirement at 65.

Another way to look at it is to see how much you can spend once retired without ever running out of money in each of the scenarios above. As long as you only spend what your investments are making in a year, you can live off your investments forever, no matter how old you get.

If you started saving at 25, you can afford to spend about $179,410 per year during retirement—and never run out of money.

If you started at 35 you can spend $84,840 per year. If you started at 45 you can spend $36,820. And if you only started at 55 you can spend $12,390 per year.

This is assuming 7% return on investment in perpetuity.

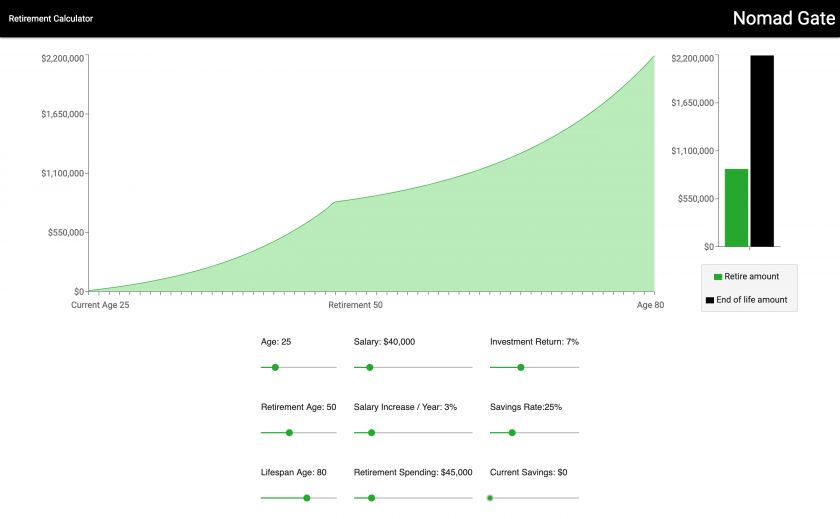

See how much you need to save for your own retirement

There are a lot of assumptions in the examples above which might not hold true for you.

I’ve published a simple Retirement Savings Calculator that you can use to estimate how much you should save for your own golden years.

While it’s not perfect by any means, I still believe it’s a useful tool to visualize the potential effect of different choices you make, such as:

- At what age you start saving

- At what age you would like to retire

- How much you put aside every month

- The effect of making investments with higher or lower expected returns

Make sure to take into account inflation when using the calculator. So if you assume that your investments will give a nominal return of 9% and you expect the average inflation to be 2%, then enter 7% as the investment return. If you also adjust the salary increase / year by the expected inflation, you can enter your retirement spending in 2019 dollars.

Give Nomad Gate’s Retirement Calculator a try now.

FIRE: What can we learn from people who retire in their 30s?

You might have heard about the FIRE movement in recent years. Perhaps you even looked into what it’s all about. If not, allow me to recap.

FIRE is an acronym for Financial Independence, Retire Early. While the ideas behind the movement originated in the 1992 book, Your Money or Your Life, it has only started picking up steam in the past decade. The mainstream media has only recently (in the past year or two) started covering the trend.

For me (and I think for most adherents of the FIRE principles), the emphasis is on the FI (financial independence) part of the acronym, and not so much the RE (retiring early) part. In other words, even though you’re trying to achieve financial independence early in life, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll stop working when you achieve it.

But why bothering with FIRE if you’re not planning on retiring in your 30s or 40s?

A digression into the future

Like many millennials relatively early in their working lives, I am feeling a certain unease about what the future will bring—especially when looking at the progress being made with automation and artificial intelligence.

While my skill set is attractive in today’s labor market, it might not be in 10-20 years. The same is true for yours.

I am lucky enough to love what I do, and as long as I didn’t have to worry about making a living I’d do it for free. In the future I might not have a choice.

With the constant progress of automation and artificial intelligence the balance between labor and capital has been shifting for several decades now (in capital’s favor) and this trend is likely to only accelerate.

This means that capital owners are likely to capture most if not all the future productivity gains, and those of us living off wages or otherwise selling our time for money will get an increasingly smaller piece of the pie.

In his book Superintelligence, Nick Bostrom argues that in the case of an intelligence explosion those with even a modest bit of (net) wealth will come out way ahead. Those with negative net wealth (more debt than savings/investments) will, put simply, be fucked.

You can opt to see this as a threat or an opportunity. I recommend the latter.

Enter FIRE.

The best way to hedge against these changes is to start building your personal wealth today and make sure the majority of it is invested in broad, global index funds. That will ensure you get your “fair share” of future capital returns.

Even if those predictions are wrong, by being prepared you will anyway be better off. So I am inclined to try to achieve financial independence as soon as possible—but not at all costs.

Even if you don’t end up retiring in your 30s or 40s, you’ll end up with a lot more (financial) freedom, have fewer worries about the future, and be able to live a healthier life.

Despite having several detractors, I think most people can learn lots of valuable lessons by studying and emulating many of the FIRE movement’s core tenets.

Here are some main learnings from the FIRE movement you should take to heart:

- Live below your means

- Be intentional about your spending

- Pay back loans, avoid credit card (or other high-interest rate) debt like the plague

- Spend smarter, not more

- Save a lot, invest your savings

- Plan for a rainy day

Many people in the FIRE community argues that a 4% withdrawal rate once retired is safe—meaning it is unlikely ever to erode the principle of your investments. That means you must save about 25 times your annual spending before you retire. E.g. if you spend $50,000/year, you’ll need $1.25 million to retire safely for good.

I think this is a reasonably conservative goal to aim for.

How to save

Hopefully, I’ve convinced you to start saving for your own future. But how should you go about it?

I’m definitely a Boglehead, and my own investment philosophy looks very much like the one advocated for by the recently late John Bogle.

Bogle was the founder of Vanguard, and while he might not have invented the index fund, he definitely popularized it.

His book The Little Book of Common Sense Investing has greatly influenced my thinking about long-term investments. It is well worth a read.

Below follows my slightly adapted version of the Boglehead method (made with nomads, expats, and other global citizens in mind):

Start investing early

If my previous examples weren’t enough, here’s another one:

If you invest $2000/year starting at age 25, you will have approximately 40% more savings at age 60 than if you start investing $5000/year at age 40. And that despite having put in $30,000 less over the years.

Take just enough risk

There is a range of different investment options available to you, some of which carry too much risk and some of which carry too little risk.

Investing your entire retirement savings in cryptocurrencies is an example of the former. Leaving all your savings in a “high” interest savings account is definitely too low risk. If you do that your return might not even be enough to cover inflation, so you will effectively lose money every year you leave it there.

The asset class that consistently has provided the best returns since the beginning of the last century is equities—such as buying stocks in publicly traded corporations. While individual stocks can be extremely volatile, the overall stock market is a bit less so (which we’ll come back to later).

For example, the US stock market (as measured by the S&P 500 index) have provided investors with an average return of about 7% per year, adjusted for inflation. That includes both ups and downs, such as the dot-com bubble and the great recession.

The stock market is great for long-term investing. Over time, you’re likely to see a better return than any other asset class, but sometimes the market experiences large corrections like the one in 2007-2008.

Since the stock market can move quickly in either direction, you might want to hold the savings you are expecting to spend over the next few years in a more stable asset class; fixed income.

While fixed income includes interest-bearing bank deposits and CDs (more on these later), perhaps the most popular variant for our purposes is bonds.

But what are bonds? In short, they are loans made to governments or other large organizations/corporations. The interest rate you get from a bond depends on the perceived risk that the creditor will default on their debt before the maturity of the bond.

Relatively safe bonds like US Treasury bills offer a relatively low yield (yearly payment divided by purchase price) since the US Government is unlikely to default on their debt, while corporate bonds issued by less financially stable companies will have a high yield to compensate for the high risk that the company defaults on its debt (making the bond worthless).

When discussing bonds in this article, I’m primarily referring to the relatively safer government bonds with low yields. The purpose of the fixed income portion of your portfolio is to provide stability and predictability, so it shouldn’t involve unnecessary risks.

The percentage of your portfolio you invest into equities vs fixed income depend on factors such as how comfortable you are with risks and fluctuating returns (will you stay cool and not sell your index funds when the market drops sharply?) and how long it is until you’ll need your savings.

A common rule of thumb for Bogleheads is to hold approximately their age in bonds, meaning if you’re 30 years old, place 30% of your savings in bonds and 70% in equities.

If you (like me) find this rule of thumb to be a bit conservative, you can adopt something like your age minus 20 in bonds instead.

And remember, it’s just a rule of thumb. If you’re planning a large investment in the near future (e.g. buying a sailboat or house) or retire sooner than most people, you may want to allocate a larger percentage in bonds.

Diversify & save on costs

We all know it’s a bad idea to put all your apples in one basket. Likewise, don’t put all your stock in Apple. Or any other company for that matter.

True, if you bet on a single company and it does incredibly well, you will too. But it might also go bankrupt. Or more likely, lose almost all of its value in the matter of months or years, and never rebound. Not a fun ride to be on.

While the technical details are a bit too much to get into in this article, investors can keep a similar expected return while reducing risk/variance (in either direction) by diversifying their portfolio.

So when I say to place most of your investments in equities, I’m not talking about individual stocks. What I’m talking about is low-cost index funds where you own a representative slice of the entire stock market.

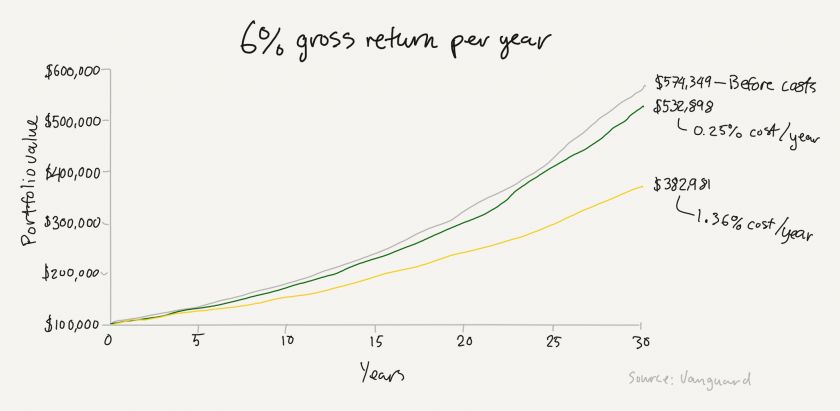

An index fund is a type of mutual fund that saves on costs by just following an index, meaning they just own a representative sample of the entire market. This way they need not hire “experts” that try to pick the best companies to invest in, meaning they can pass on these savings to you. A typical index fund has a TER (total expense ratio) of anywhere from 0.01-0.50%, while actively managed funds can have TERs of 1-3%.

Because of these lower costs, over time index funds tend to outperform nearly all actively managed funds.

Depending on where you live, it might not be possible or desirable to invest in index funds directly. A very common option is to own an index ETF. ETFs are pretty much the same as index funds, except that they are traded on a stock exchange. This means that the price of ETFs vary throughout the trading day, while the price of index funds are only updated at the end of the day (based on the net asset value of the underlying funds).

In practice, this doesn’t matter that much, and you should choose the type that is easier for you to trade, has lower transaction costs and are most tax favorable for your personal situation.

ETFs in some countries (particularly in the EU) come in two flavors: accumulating and distributing. In the former any dividends paid by the underlying companies are reinvested into the fund automatically, while in the latter they are paid out to you. I’ll get back to this later in the article.

Don’t try to time the markets

“Time in the market is better than timing the market”

One rookie mistake many first-time investors make is that they try to time the market—meaning they try to buy low and sell high by waiting for the “perfect time” to trade.

That sounds great in theory, but in practice it’s very hard to get right. Most of the time you’ll end up waiting too long to buy into the market. You might tell yourself that it must surely start falling soon… So you wait, and wait, and wait—while the market keeps climbing. In the end you regret not buying sooner.

And even if you manage to buy low, selling at the peak is even harder. You’re much more likely to sell way too early, or way too late.

Sure, for some professional investors who buy individual equities (not index funds reflecting the entire market), it makes sense to time their trades. While even most professional investors don’t beat the market over the long run, no one would hire them if they didn’t try.

But you, my dear reader, do yourself a favor… Don’t try to time the market. With an investment horizon of 10 or 20 or 40 years, time tends to heal all wounds.

Keep in mind all the time you save by just buying and holding index funds/ETFs reflecting the whole market, compared to actively managing your portfolio. Even if you could (but probably wouldn’t) get an additional return of a percentage point or two—by spending that time in your regular profession instead you could save much more and get an even larger return.

So focus on what you’re good at—your profession. Leave your long-term investments in the caring hands of time.

If you need more convincing, check out these market timing games.

Pay down debt

This might go without saying, but if you have debt—especially high-interest debt—paying it down should be your first step to financial independence.

If you have credit card debt (often costing you 15-25%/year), paying it back ASAP should be your number one financial priority. There’s no point in starting to invest (at an expected annual return of 7%) when you have a fire burning in your wallet. Put out the fire first.

When you start looking at the part of your debt with a substantially lower than 7% annual interest rate, you could make the argument that it makes more sense to invest your savings than paying down the debt. And from a purely utility-maximizing perspective (hi there, homo economicus) you’d be right.

However, if you are looking to gain greater control over your finances and be less sensitive to external forces, it might make sense to pay it down, anyway.

In my case, I still have about €25,000 in student loan debt that’s costing me about 2.5% per year. While I could sell a large chunk of my investments to pay it down today, I see paying it down as an alternative to adding to the fixed income (bond) part of my portfolio. (Note: this isn’t a perfect replacement, as it won’t leave me with cash to invest into equities when rebalancing my portfolio in a market downturn.)

So every month I allocate about the same amount that I would have allocated to bonds and pay down my student loans instead. Yet, instead of paying it back over the default 20-year period I’m paying it back in just a few years.

Live below your means

While some people in the previously mentioned FIRE community seem to delay living their life until they retire (by refusing to spend money on anything), there are several more enjoyable ways to live below your means and reach financial independence early in your life.

Below I will take a closer look at a few ways that can help you save 20%-80% of your income while still enjoying your life to the fullest.

Geoarbitrage

Perhaps the most common way for digital nomads to achieve early retirement without sacrificing life quality along the way is to work remotely for a company with “western” salaries, while spending most of their times in cheaper countries.

There are plenty of cities around the world offering a high quality of life for less than $20,000 per year. If you couple that with a remote job paying $50,000-$100,000—or even more—you can easily put most of your paycheck towards your financial independence goals.

Become a small business owner

While entrepreneurship definitely isn’t for everyone, it can be a rewarding path to financial independence.

Plenty of nomads, expats, and PTs make a living from their small businesses. Whether your goal is to build a profitable one-man business (like Nomad Gate), or a company with lots of employees doing most of the work, it can put you on a path to financial independence and early retirement.

Not only that, but building a product or service that people find valuable can feel immensely meaningful. I don’t mean to go all Viktor Frankl on you, but in terms of life satisfaction that’s a biggie.

Optimize your taxes

“In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes”.

– Benjamin Franklin

While most people have no legal ways of reducing or completely avoiding taxes, as a nomad, expat, or perpetual traveler (PT) you have several options.

Turns out good ol’ Ben Franklin was wrong.

The most important is to choose wisely the place you call home—if you even have a fixed base at all.

The single most potent weapon you have to legally reduce your tax liabilities is to move or set up your main residency in a friendly country.

Some jurisdictions to consider (depending on your personal circumstances): Malta, Portugal, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Paraguay, Georgia, Thailand, the Philippines, etc.

Note that taxes for Americans are more complicated, yet come with some additional opportunities.

Invest your cost of living and tax savings

If you’re from a high cost/tax country—or you think you might want to relocate to one in the future—I recommend that you pretend you’re already living there.

Once you become location independent, it’s easy to fall into the trap of getting comfortable with a lower level of income and savings when spending most of your time in lower cost (and lower tax) locations.

While it’s nothing wrong with moving to Chiang Mai and realizing that you can live perfectly well on $1,000 a month and pay very little taxes, if you don’t aim for more you will eventually start feeling trapped.

You might think you will never want to move back to your home country, but what if you’re wrong?

Perhaps you’d like to move back to be closer to your parents as they age, or to access higher quality health services as you age yourself.

Even if you’re from a lower cost country, you might want to spend your later years in a more developed and stable region.

Or even if you don’t, it’s nice to at least have the option.

So here’s what you do:

Say you are a remote worker making $80,000 per year before tax. In your home country (which you might want to return to at some point) your tax bill would have been $35,000 per year and your expected living costs another $40,000.

You move to a low-tax, low cost country. You keep your $80,000 salary, but only pay $8,000 in taxes and another $17,000 in living costs.

Now, pretend that your tax bill and living costs were still the same as in your home country. Put the entire difference—the $27,000 tax savings and $23,000 cost-of-living savings ($50,000 total)—into your own retirement fund.

Where, what, and how to invest

Now that you know why you should invest a large part of your salary into low-cost index funds (and some in bonds as you age), let’s look at:

- Where to invest (choice of broker)

- What funds you should invest in (choice of domicile, fund type, index, stock exchange)

- How to invest and execute trades

Where to invest

Where you invest can have a large impact on your final results. One of the main ideas behind low-cost index funds is to reduce transaction fees as much as possible, but besides the management fees charged by the fund (TER—total expense ratio) your broker will usually also slap on some fees.

Shortcuts

What works for you will depend on a lot of factors, most importantly where you live and what your goals are.

In this section we’ll look at which brokers you should use to minimize fees, simplify your paperwork and tax returns, and which are easy to use.

United States

If you live in the US, you have access to a wide range of good brokers, many of which are very affordable and with a wide range of index funds and ETFs to trade—often for free.

Below I’ve listed some of the most popular.

M1 Finance

M1 Finance is basically a hybrid of a broker and a bank account. It aims to be the one place where you can manage all aspects of your financial activity (save, invest, spend, borrow)—and it’s becoming more and more popular.

You will be able to construct your investment pie made up of stocks (also fractional) and ETFs, add money automatically, and rebalance any time with one click. All of this, you can do for free. You can also choose among 80 ready-made portfolios if you don’t want to pick out individual equities yourself.

With M1 Finance, you can also execute separate buy/sell orders, but these will be performed during a certain trading window (for a basic account in the morning).

M1 Finance provides a checking account, a VISA debit card, and you can borrow money at low rates (2-3.5%) when your portfolio is at least $10,000.

If you have an M1 plus account, they will pay 1% both for keeping money in your checking account and spending it (cashback). The plus account fee is $125 per year.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| All your financial activities in one place | Minimum account balance $100 to get started |

| Free and automated investing in stocks and ETFs, free and easy rebalancing | |

| Comes with a checking account and a debit card | |

| Attractive borrowing rates | |

| 1% cashback and APY with an M1 Plus account |

Read more (Wikipedia)Open M1 Finance account

Vanguard

Vanguard is extremely well-liked in the investing community. As previously mentioned they were founded by John Bogle and pioneered the index fund. To this day most people consider their index funds to be the best available.

Vanguard is best known in the US, but they now also accept clients from Canada, Mexico, most EU/EEA countries, UK, Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, and China.

You can buy their ETFs for free, but you have to pay the transaction fee for stocks. While they don’t charge any fees if you invest in their mutual funds, it usually requires a $3,000 minimum investment. They have no account or inactivity fees.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Offers some of the best/cheapest funds on the market | No physical branches |

| Unique ownership structure aligning their interests with yours | No longer the undisputed winner on price (but never far off) |

| Excellent fund coverage |

Read more (Bogleheads Wiki)Open Vanguard account

Fidelity

Another popular broker is Fidelity. Many people love their customer support, and they also offer a long list of commission free ETFs to trade in.

Fidelity also has physical branches in many cities, so if that’s something you value then it might be a good choice.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Mutual funds and ETFs competing with Vanguard on cost | Their funds aren’t always as tax efficient as their Vanguard counterparts |

| No minimums for purchasing their mutual funds | |

| Extensive network of physical branches |

Read more (Bogleheads Wiki)Open Fidelity account

Charles Schwab

If you already have and use their excellent checking account and want to minimize the amount of financial accounts you maintain, then why not also use them for your retirement savings?

They might be slightly less popular in the community than Vanguard and Fidelity, but that might be about to change: As of October 7, 2019 they are removing all commissions for equities in the US and Canada.

They also have physical branches across the country—so if it’s important to you, check if they have a branch near you.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Their own funds have very low expense ratios, usually undercutting Vanguard with 1-2 basis points | Not as good fund coverage as Vanguard |

| Amazing checking account with free ATM withdrawals and no FTF | |

| Extensive network of physical branches | |

| Zero commissions for trades on US and Canadian exchanges | |

| Also available outside the US ($25K min. deposit required) |

Read more (Bogleheads Wiki)Open Charles Schwab account

Europe

The broker market in Europe is very fragmented, and there are a lot of local brokers across the continent. I won’t be covering all of those in detail, but instead take a look at some that can be used across most of Europe.

Note that tax reporting requirements for ETFs and index funds vary across Europe, and in some cases it’s worth paying higher fees to a local broker in return for getting all the tax reporting done for you. This can be the case in e.g. Austria and Germany (not an exhaustive list).

DEGIRO

If you have a bank account (or registered business) in one of 18 European countries, you can get an account with what must be one of Europe’s favorite discount brokers.

They have a range of ETFs that you can trade twice per month—once in each direction—for free (conditions apply, check DEGIRO’s site). The list of free ETFs varies a bit depending on which country account you open but you can see an example (for an Ireland account) here.

DEGIRO is also great if you want to buy individual stocks, offering access to 50+ exchanges to choose from. Their transaction costs for US stocks are only €0.50 + USD 0.004 per share. Fees for other markets are a bit more, but also very reasonable.

You can choose between two main profiles with DEGIRO: Custody or Basic. With the Basic account, DEGIRO may lend out your shares to other investors, who want to short those shares. This isn’t a huge risk, but it’s something to consider. If you opt for their Custody account, your shares won’t be lent out, but you will have to pay a fee to receive dividends. If you only buy accumulating funds, this shouldn’t impact you and you may as well opt for the Custody account.

If you need more help with choosing an account type, check out this Reddit thread for some tips.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| One of the lowest cost options in Europe | May lend out your shares with the Basic account |

| Fairly good list of commission-free ETFs | Only one base currency |

| Access to most important markets | Custody account has fees for receiving dividends |

Investing involves risks of loss.

MeDirect

If you don’t have a bank account in any of the countries supported by DEGIRO (and don’t care to open one) you should consider MeDirect, a Maltese investment bank.

While their trading fees aren’t as low as DEGIRO (usually around 0.1% with a €10 minimum), they don’t charge any custody fees or inactivity fees, making them a good choice for someone with a buy and hold strategy who only invests occasionally (not necessarily monthly). Since May 2020 they also let you invest in mutual funds with no minimum fee, just 0.5% of the transaction, making it more attractive for those who place smaller orders.

You can open an account either online or in person at a branch in Malta and the process is very easy. Accounts are available to all EEA residents, except US persons (i.e. citizens and green card holders).

For a higher fee (typically 0.6% with a €30 minimum) you can instruct MeDirect to execute trades on your behalf. They will probably recommend that you invest in funds with a higher cost than index funds/ETFs, but if you insist they will still buy the low-cost index funds you ask for. For most of us it probably makes more sense to trade ourselves, but if you want to automate the process (and avoid keeping track of short-term movements of your investments) it may be worth the extra cost.

As a bonus, they also offer decent banking features, such as debit cards and high-interest term deposit accounts.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Easy to open for EEA/EU residents | Trading fees could be lower |

| Easy to use | |

| Possibility for managed/advisory accounts | |

| No custody or inactivity fees |

Read more (Wikipedia)Open MeDirect account

Scalable Capital

Scalable Capital is known for having one of the most established robo-advisors in Europe and recently started also offering broker services.

Their uniqueness lies in making ETF savings plans—which are very popular in Germany—available for everyone with a SEPA account. The only exceptions being US persons and Swiss residents.

It works like this: You choose a certain amount that will be automatically pulled from your bank account and invested into your preferred ETF (or ETFs) every month. You don’t have to lift a finger—as easy as pie!

Don’t worry if you prefer to trade more often or don’t want to use savings plans; they got you covered too.

If you only use one ETF, it will be completely free of charge. For additional ETFs or manual trades there’s a fee of €0.99, with subscriptions available that give you an unlimited amount of trades starting from €2.99 per month.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Low costs | €250 minimum for trades, €25 for savings plans |

| Offers free savings plans | Not available for business accounts |

| Can buy fragmented ETFs with savings plans | Does not support multiple currencies, only euros |

| Easy to switch between pricing options | The online interface is in German |

| Only supports the gettex exchange (which mirrors Xetra), which may not always give you the best spread |

LHV

If you’re one of the thousands of digital nomads with Estonian E-residency and an Estonian company, it might make sense to invest through LHV—especially when starting out.

If you’re already banking with them and are using Xolo (formerly LeapIN) for managing your business it’s especially attractive, since the amount of additional “paperwork” will be minimal on your part. (Xolo integrates with LHV and will import your transactions automatically.)

Their transaction fees for investing in foreign equities used to be quite high compared to brokers but recently they have lowered their prices. Trades will cost 0,14% (with a minimum of €9). So, you’re better off investing in amounts starting from €1000 (to keep the fees reasonable). They are still not quite as affordable as discount brokers, but very competitive compared to other banks.

There is also a management fee of 0,01% for holding foreign securities. For private persons, the management fee starts for portfolios over €50,000.

Do you already have more than $100,000 in company assets you want to invest, or are investing large chunks of money every month? Consider using Interactive Brokers instead (mentioned below) as the fee savings would be significant.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Good starting option for Estonian e-residents | High fees in most markets |

| Integrated with Xolo | |

| Simple and fairly easy-to-use interface | |

| Access to most important exchanges |

Read more (Wikipedia)Open LHV account

World

While there might be good local alternatives where you live, it’s outside the scope of this article to explore those in great detail. If you have any tips to local brokers, please leave them in the comments!

Depending on where you’re from and the amount you are investing, some brokerages mentioned above might also be willing to take you on a client.

Interactive Brokers

A very good, low cost broker available in most countries around the world. They also accept business clients, in case you’re saving up through a legal entity.

But even though their transaction costs are among the lowest in the industry, you need to watch out for their monthly minimum fees! They will charge you a minimum of $10 per month, unless you already paid more in commissions than that or have more than $100,000 invested with them.

They used to have a minimum account opening balance of $10,000, but that’s no longer the case. Still, because of the monthly minimums, it’s a broker that’s more suitable once you have more invested or are investing a good chunk of money every month.

If you don’t have any good local alternatives where you live (costing you less than $10/month in trading fees) I would recommend giving Interactive Brokers a try.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Available nearly worldwide | $10 monthly minimum commissions (unless $100K+ assets) |

| Access to most important markets | Not the nicest user interface |

| Very low trading costs | Lengthy and convoluted signup process |

| Extremely low currency exchange costs |

Read more (Bogleheads Wiki)Open Interactive Brokers account

Trading 212

A increasingly popular broker specializing in so-called “CFDs” (an instrument I wouldn’t recommend unless you know what you’re doing) through their product Trading 212 CFD. Instead, just disregard this part of the product and sign up for Trading 212 Invest, where they offer over 3000 no-commission ETFs.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Available nearly worldwide | Not available for US citizens or residents |

| Commission-free ETF investing | Not the best selection of markets |

| Relatively user friendly | |

| Free debit/credit card topups |

What to invest in

When it comes to what funds to invest in there are a few important decisions you need to make:

- Which index do you want to track?

- What fund domicile is most tax effective?

- Should you prefer accumulating or distributing funds?

- On which stock exchange does it make sense to buy the fund?

Let’s go through each, plus a few other considerations.

Shortcuts

Choice of index

Let’s take a step back. What do we even mean by an index?

It’s a representative list of companies in either a single market (or market segment), or several markets across the globe.

There are indexes designed to reflect a representative sample of the global stock markets (e.g. the MSCI World index) or a particular country (e.g. the S&P 500 index).

An index fund is a particular type mutual fund that’s designed to track a—usually market value weighted—index as closely as possible.

By tracking we mean that the fund tries to mirror the performance of the index as a whole—something it does by investing in all the companies included in the index in proportion to their value (a.k.a. market capitalization or just market cap).

Since these funds blindly follow an index, we call them passively managed. This means you don’t pay a premium for the fund to hire expensive stock pickers, who—on average—do a poor job of beating the index, anyway.

You have indexes focusing on the whole market and indexes focusing on specific industries or company sizes. I would recommend buying index funds or ETFs that track as broad of an index as possible, ideally a global one.

You could buy several index funds—each covering a part of the world (US, EU, developed, emerging markets, etc)—or you can pick one that aims to reflect a representative selection of the whole world (which is usually the easiest).

Since the most valuable companies are based in developed nations—the US alone being responsible for almost 55% of the market capitalization in the FTSE All-World index, while all emerging markets combined are only responsible for about 10%—by investing in a global index fund you are still mostly exposed to developed markets.

Some popular indexes to consider for you portfolio:

- MSCI World: Includes stocks from 1,655 companies across 23 developed countries. Despite its name it does not include emerging markets.

- MSCI Emerging Markets: Includes stocks from over 800 companies across 26 emerging markets.

- FTSE All-World: An even wider index which includes about 90-95% of the investable market in both developed and emerging markets.

- S&P 500: Includes the 500 largest publicly traded companies in the US. An alternative is the S&P Total Market Index which includes most public companies in the US, including small cap and micro cap stocks. You can combine these with the FTSE All-World ex-US index to get global coverage.

Note that MSCI and FTSE differ a bit regarding which countries they classify as emerging or developed, with the former still classifying South Korea and Poland as emerging markets. Therefore, you shouldn’t mix an MSCI developed index (e.g. MSCI World) with an FTSE emerging index (e.g. FTSE Emerging Markets) or vice versa (you’d be getting either double or no exposure to South Korea and Poland).

Personally I like to keep it simple, and if possible I prefer to buy a single fund following a global index.

However, depending on which funds you have access to (as well as trading costs and expense ratios for those funds), or if you don’t want to be exposed to the world markets in the same proportion as the popular indexes, you may still be better off mixing and matching funds to get the exposure that you desire.

Fund domicile

The next thing you need to decide is where the funds you invest in should be domiciled. The domicile of a fund is where it is registered and administered from (meaning it’s often not the same as where your broker is based).

What fund domicile you pick will have a significant impact on your tax liabilities and which funds you can access. While the US is the country with by far the most funds, for several reasons they may not always be the most appropriate for every situation.

Two popular domiciles are the United States and Ireland—but for different reasons.

The United States

The US is home to the most diverse selection of funds you will find anywhere. And because of more competition the funds here are often lower cost than their cousins elsewhere.

Still, there are some disadvantages—especially for non-US resident investors—that may make you want to choose another domicile:

- The US has a withholding tax rate of 30% on dividends (may be as low as 10% for some countries thanks to favorable tax treaties).

- The US also has an estate tax rate of 40% on US situated holdings above $60,000 for non-US residents.

- US domiciled funds are required to always distribute the dividends they receive, which isn’t ideal if you prefer accumulating funds (more on that below).

If you’re a US citizen, living in the US, you are probably best off buying US funds. The same goes if you live (and plan on continue living) in Japan—the only country with a US tax treaty with a 10% withholding tax that also covers estate taxes.

If you’re neither tax resident in the US or Japan, you should at least consider funds domiciled outside of the United States.

Note that if you are based in Europe, chances are that it’s very hard (if not impossible) for you to buy US domiciled funds, since they usually don’t provide the key information documents required for packaged retail investment and insurance products (PRIIPs) in the EU since 2018.

Don’t worry though, there are plenty of good EU domiciled funds. And although their expense ratios tend to be slightly higher than their US counterparts, you will generally save some money on currency exchange and maybe even taxes.

Ireland

For those looking beyond the US, Ireland is one of the most attractive and popular domiciles—particularly for ETFs. This is in large part due to the favorable tax treatment and business environment available for funds there.

Not only is there no withholding tax on earnings from Irish funds (except on Irish assets), the funds also pay no corporate tax in Ireland. In addition, Ireland has a reasonably favorable tax treaty with the US, meaning that Irish funds pay only 15% withholding tax on US dividends.

This among the most favorable rates available—only Bulgaria, China, Japan, Mexico, Romania, and Russia have a better deal at 10%. However, like previously mentioned, of these countries only Japan has a US tax treaty covering estate taxes.

The one thing you miss out on when investing in US companies through an Irish domiciled fund or ETF is the ability to deduct paid US withholding tax on dividends from your personal taxes where you live. This, of course, is only relevant if you pay taxes in the first place.

So, which domicile to pick?

If you…

- don’t live in the US or Japan, and

- live in a country with a favorable US tax treaty, and

- you pay a significant amount of tax in your current home country which could be offset by the dividend withholding tax paid to the US, and

- don’t plan on moving countries anytime soon

…then you may be better off investing directly in a US domiciled fund for the US part of your portfolio (and use an Irish fund for the non-US part).

And depending on your residency you should only do so for the first $60,000 invested in the US.

However, if you have organized your life in such a way that you pay no or very low taxes, you might be resident in a country with a less than ideal (or non-existing) tax treaty with the US. You may also not pay much tax, so there may not be anything to offset the US withholding taxes against. In this case, avoid the US as a domicile altogether.

I realize this might seem a bit complicated, but by looking at the Nonresident alien’s ETF domicile decision table on the Bogleheads Wiki it should become easier to determine what you should do.

Finally, you should also check if there are any specific tax treatment of funds depending on their domicile wherever you are resident at the moment.

One example is the UK, where your gains in any non-reporting offshore fund (meaning funds registered outside the UK which don’t report directly to the UK authorities) are taxed at normal income tax rates, rather than the lower capital gains rates.

Still, you shouldn’t over-optimize for your current residency if you have any plans of moving elsewhere in the future. Make sure the assets you invest today in can move with you tomorrow without significant negative effects.

TIP: You can identify the domicile of a fund by looking at the two first letters of its 12-digit International Securities Identification Number (ISIN). If it starts with US, it’s from—you guessed it—the United States. Irish funds will start with IE, British with GB, and so on.

Accumulating vs distributing funds

Especially if you’re investing from Europe, you might encounter the terms accumulating and distributing when researching which funds to invest in.

The difference is simple: A distributing fund will pay out all the dividends it receives from the underlying companies as dividends to you. You can then either spend this money, or manually reinvest it. This is the traditional way of doing things.

On the other hand, an accumulating fund will not pay out the dividends, but reinvest them into the fund on your behalf—meaning that the value of the fund (and your fund units) increase faster.

Disregarding the effect of transaction costs, taxation, etc, having a distributing fund and manually reinvesting the dividends should give you the same performance as holding an accumulating fund.

So which should you choose?

Again, it depends.

First off, the tax treatment differs between countries.

In some countries (like Belgium) you’re better off with accumulating funds. If you pay a higher tax rate on dividends than you do on capital gains, and your country of residence doesn’t deem the accumulated dividends virtual dividends (and still tax them as if they were actually paid out), then you should prefer accumulating funds.

If you’re currently living in a country with a) no personal exit tax, b) significant tax on dividends, and c) you’re planning to move elsewhere (to a country with no capital gains tax, or that will only tax you on the gains since you moved to the country), then you should also prefer accumulating funds.

In other countries (e.g. the UK and Switzerland), both types of funds are taxed at the same rates. In these countries you’re taxed on the accumulated dividends as if they were actually distributed. This may or may not require some effort on your part to keep track of and report. You’d also need to remember to deduct the tax you already paid on dividends when calculating your capital gains tax when you finally sell the fund—if not you’d be double taxing yourself.

In these cases you might be better off with distributing funds (assuming low transaction costs, as well as the price and expense ratio of both options being the same) in return for simpler reporting.

Finally, there are cases like Germany, where you might be better off with a combination of both. Since 2018 Germany has been taxing your accumulating funds as if a fictional dividend was paid (“advance lump sum”) every year. However, this lump sum is not based on the actual dividends of the underlying assets, and is often less than the actual dividends reinvested in the fund, meaning you still get a slight advantage by delaying part of your tax payments until the day you sell the fund (or avoid it altogether if you move from Germany). Still, in Germany (and many other countries) you also have a tax-free allowance for dividends, meaning you may want to hold enough distributing funds to claim this allowance every year.

Note: In cases where holding accumulating funds complicate your tax reporting, you might be better off using a local broker than the ones I discussed above—especially if they automatically do all the tax reporting on your behalf.

If you want to dig even deeper on this topic, check out these two articles:

- Should I choose accumulating or distributing funds? (Index Fund Investor EU)

- Distributing Funds vs Accumulating Funds: Which is better? (The Poor Swiss)

Choice of stock exchange and currency

When you buy units in a mutual fund, you typically buy them directly from them directly from the provider (e.g. Vanguard). However, ETFs are traded on a stock exchange—just like regular stocks—hence the name: Exchange Traded Funds.

So, at which exchange should you buy your ETFs?

While your choice of exchange generally isn’t relevant for your tax liability (where the fund is domiciled is what matter for that), it may impact your direct and indirect trading and transaction costs.

After you’ve chosen what index you want to track, and made a shortlist of attractive funds that track that index, the next step is to look at which funds are available through your broker at which exchanges.

If you’re using a local broker, you may not have a choice in the matter—perhaps they are only working with one exchange.

But if you have a choice, then look at the following on each exchange available to you:

- Trading currency

- Trading volume for each ETF

- Transaction costs

Let’s go through each in more detail. Just keep in mind that with a long enough investment horizon these factors become less important than the ongoing expense ratios.

Trading currency

The currency you trade in might matter less than you think.

Let’s get one thing straight first: The return of the fund as measured in your home currency depends on how the underlying assets (the individual companies) perform compared to your currency—not how the currency you trade in performs compared to your currency. The currency of the fund (which may differ from the trading currency, often USD) also does not matter.

Note: It makes little sense to buy equity funds hedged to your home currency, although you may consider that for the bond/fixed income part of your portfolio.

Where currency matters is when you convert from the currency you have to the currency you will pay for your investments in, and the final conversion (after you sell your investments) to the currency you’re planning on spending the money in.

These costs vary from broker to broker. Some will allow you to deposit any currency that you’d like (meaning you could convert your funds for cheap using a service like Wise before depositing them with the broker). Some brokers also offer very competitive exchange rates themselves (could be 0.5% or less markup).

Others may force you to exchange your money with them at extortionate rates of 2% markup or more—meaning a total loss of 4% for two conversions. Ouch.

If you’re still confused by currency effects on performance, read Non-US investors and ETF currencies on the Bogleheads Wiki for more detailed explanations and examples.

Trading volume

The trading volume (i.e. how often an ETF is bought and sold) varies from exchange to exchange. This leads to two effects:

First, the higher volume, the smaller bid/ask spreads you’ll see. This is the difference between the highest price a potential buyer is currently willing to pay, and the lowest price any potential seller is willing to accept.

Second, with a higher volume you’ll be able to buy and sell a bit faster. This is rarely an issue for our purposes, though.

While the impact of these two effects is usually small for most large ETFs, for smaller ones it may be more noticeable. Another reason why preferring larger, more popular funds makes sense.

Transaction costs

Next, you should consider how much your broker charge you for trading on each available exchange.

There’s often a home bias where brokers offer lower rates when trading on a local exchange. But if the local exchange doesn’t have the ETF you’re looking for (or an acceptable replacement with a low TER—total expense ratio), then you’re probably better off accepting slightly higher transaction costs on a different exchange.

Some brokers (e.g. DEGIRO in the EU) will offer commission free ETF trades on specific exchanges, so check if you can find the fund you’re looking for included in their offer.

If a broker charge a high fixed or minimum cost per trade on the exchange you prefer, it may also impact how often you trade (see the case of LHV above)—especially if you’re only able to save a low amount every month.

Other considerations

As I’ve alluded to above, I prefer larger, more established funds when available, for a few reasons:

- A large, established index fund is less likely to close, triggering unwanted taxation of capital gains.

- Large funds often have lower expense ratios while still being profitable due to economies of scale.

- They also tend to have larger trading volumes (leading to lower bid/ask spreads).

Whether or not you think a fund will stay around for the long run becomes extra important if you currently live in a country with high capital gains taxes—but no exit tax—and are planning to move to another country where you can liquidate it without paying any tax.

A note on bonds/fixed income

While I haven’t talked too much about bonds so far—which is the most common recommendation for the fixed income portion of your portfolio—they are still an important part of our long-term investment strategy.

The obvious purpose of bonds is to provide stability, and hence it makes sense to increase the percentage you allocate to bonds when approaching a time where you are planning to withdraw large parts of your investments (either for large expenditures or planned retirement—whenever that may be).

A perhaps less obvious purpose of bonds is to help you time the market—as if by magic.

But wait, didn’t I say over and over not to try to time the market??

Yes, and that’s true. But by holding a fixed proportion of bonds (which you achieve by periodically rebalancing your portfolio) it’s not really you who’s timing the market. (Plus, you could argue that it’s not market timing, but cycle timing.)

The best time to buy an asset is when the price is low. When the price of equities fall (e.g. during the last financial crisis), in order to rebalance your portfolio you need to sell bonds and buy more equity index funds—exactly what you should be doing.

If you had all your savings in equities, you won’t have any spare cash to ramp up the buying when it makes most sense.

Conversely, during a market mania when everyone and their dog are buying equities, driving the price way above reasonable levels—like during the dot-com bubble—you’d be forced to move assets from overpriced equities into bonds to rebalance.

While I won’t claim that this effect completely makes up for the loss in expected return by holding bonds instead of equities, at least it makes the tradeoff for more stability easier to swallow. In the end you give up less long-term returns than you would otherwise expect—all without actively trying to time the market.

What to look for in bonds and bond funds

Just like with equities, you can buy low cost bond index funds or ETFs. This is often much more convenient than buying individual bonds, but it comes with certain tradeoffs.

A bond fund doesn’t behave the same way as if you invest in an individual bond (which would pay back your principal at maturity). Rather, it’s like a bond ladder, where the fund invests in new bonds as old ones matures, keeping a usually constant duration. Going into more details here is outside the scope of this article (so much can be said about this topic), but if interested you can read more on the Bogleheads Wiki.

For the rest of the article I will focus primarily on bond funds and ETFs, as that’s usually the most practical option—particularly for international investors.

When picking your bond ETF, look for one investing in assets with mostly low credit risk (i.e. prefer AAA rated and other investment grade bonds). While a lower-rated bond will have a higher return, this part of your portfolio is meant to be risk free. Bond issuers with a lower rating have a much higher likelihood of defaulting on their debt, making the bonds ultimately worthless.

You should also prefer intermediate-term bonds as these historically have had significantly higher yields than short-term bonds, and about the same as long-term bonds (but with lower risk).

Currency and hedging

Since the purpose of bonds is to provide stability in your finances, it’s often recommended to hold bonds in the currency that your upcoming financial obligations are. If you’re currently living in Australia, but are planning to retire in the United States—get bonds in US dollars.

To increase diversification it can be a good idea to also buy international bonds, hedged to the needed currency. This increases costs by a little, but since currency markets are typically twice as volatile as bond markets it’s worth it for the extra stability.

Note that one effect of the hedging is that over time the returns of currency hedged bonds tend to be similar to bonds issued in that currency. Still, even though the long-term returns are expected to be similar, it’s worth the extra effort for the diversification benefits.

Other fixed income assets

While bonds are the canonical fixed income investment in the Bogleheads and FIRE communities, it’s not the only option and may not always be the best for your circumstances.

At times you can get a higher (or at least similar) return with a high-interest savings accounts, CD (certificate of deposit), or fixed-term savings account. In the former you can access your savings freely (sometimes with a limit of withdrawals per month), while for CDs and term deposits you commit to depositing the money for a fixed term (early withdrawal incurs a penalty, if at all possible).

CDs and term deposits can be used to diversify from bonds or bond funds, but I don’t think it’s a necessity for most. One important quality of savings accounts and CDs is that your deposits are typically insured up to a certain amount per bank (e.g. $250,000 in the US and €100,000 in the EU).

I think it’s a good idea to use regular savings accounts for your emergency fund (which should cover at least 3 months of expenses). Do some research into which bank offers the best rates in your market.

Example portfolios

What investments you should make depend on a lot of factors—such as your specific goals, time horizon, residency, and plans for the future—meaning it’s futile for me to suggest a portfolio that would work for everyone.

Still, I will give a few suggestions for simple portfolios that would work well for most people.

These portfolios are designed to be as simple as possible, while still being properly diversified and offering a high expected return over time.

US resident portfolio

Equities:

Buy the desired split between US and international stocks (I’d suggest about 55/45) by using these two ETFs:

Fixed income:

Either just buy this single ETF:

Or, if you want a different split between domestic US and international bonds, buy these two individually:

Non-US resident portfolio

While it varies what you have access to outside the US, it seems actual mutual index funds are a bit harder to come by and often less attractive than in the US. So for many of us it makes sense to stick to index ETFs instead.

Equities:

To keep things really simple just get this one ETF:

- Vanguard FTSE All-World UCITS ETF (exists in both distributing and accumulating varieties)—0.22% TER

Or if you want to minimize your expense ratios even further at the cost of a bit added complexity—or if you want a different developed vs emerging market split—buy one of these combinations:

For accumulating funds:

- iShares Core MSCI World ETF USD Acc—0.20% TER

- iShares Core MSCI EM IMI ETF USD Acc—0.18% TER

For distributing funds:

- Vanguard FTSE Developed World UCITS ETF—0.12% TER

- Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets UCITS ETF—0.22% TER

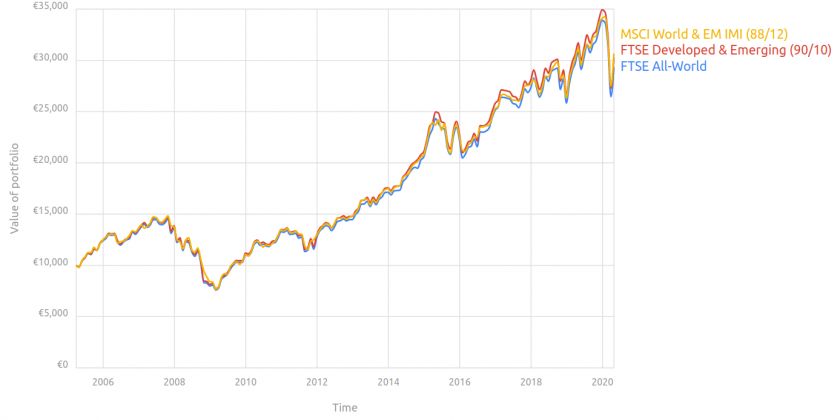

If you want to follow the free float market cap for your developed vs emerging market split, you should invest about:

- 88% into a MSCI World fund and 12% into a MSCI EM IMI fund, or

- 90% into a FTSE Developed World fund and 10% into a FTSE Emerging Markets fund.

The reason for the different MSCI and FTSE splits is (like previously mentioned) that MSCI defines Poland and South Korea as emerging, while FTSE defines them as developed.

As you can see in the following backtesting analysis from Backtest, all three portfolios have behaved very similarly in the past. Since 2005, they’ve achieved an average annual return rate of around 7.5%.

Fixed income:

This portion of your portfolio really depends on the currency where you’re planning to retire or have large future expenses.

Try to find a fund invested in or hedged to your chosen currency with a low TER (less than 0.10%) and investment grade bonds.

If you’re planning on retiring in the eurozone, I’d suggest you follow Index Fund Investor EU’s advice and pick up one of the following:

- iShares Core Global Aggregate Bond UCITS (EUR Hedged)—0.10% TER

- SPDR Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond (EUR Hedged)—0.10% TER

- Vanguard EUR Eurozone Government Bond UCITS—0.07% TER

Deciding on your equity/fixed income allocation

Let’s briefly take a step back and take a look at one of the most important investment decisions you’ll make: the percentage you allocate to equities vs fixed income.

As mentioned above, equities have a higher expected return—but they are also more volatile. Fixed income funds generally have a lower return, but stabilize your portfolio.

The following chart, also sourced from Backtest, illustrates this. It shows the evolution of three different portfolios:

- 100% equity (88% MSCI World and 12% MSCI Emerging Markets IMI)

- 100% fixed income (100% Bloomberg Barclays Euro Aggregate Treasury Bond)

- 50% equity and 50% fixed income (50% Bloomberg Barclays Euro Aggregate Treasury Bond, 44% MSCI World and 6% MSCI Emerging Markets IMI)

The portfolio with 100% equity (blue line) results in a higher return—but the road to get there is not for the faint of heart. It goes up and down a lot more than the 100% fixed income portfolio (red line). The 50/50 portfolio (yellow line) also lags behind the 100% equity portfolio, but not as much. It’s also more stable, but not as much as the 100% fixed income portfolio.

How you decide on your allocation depends primarily on two things:

-

Time horizon. How long will you invest for? If you are planning to invest for multiple decades, you have time to recoup losses from a downturn. In that case, you can afford to dedicate a higher portion to equities so that you obtain a higher return.

-

Investor psychology. Equities are more volatile and can result in higher temporary losses. For instance, the FTSE All-World index lost -18.5% of its value in a single month, in October 2008. If such losses would cause you to panic and sell your investments, it’s best to allocate a higher portion of your portfolio to a fixed income fund.

How to invest

Now that you know why you need to start saving and investing ASAP, and you also have some idea of what you should invest in, let’s take a look at how to invest to maximize your chances at success over the long term.

Shortcuts

Automate and minimize friction

As you should know by now, one of the hardest parts (if not the hardest part) about this investment strategy is to stay the course—especially if your investments suddenly drops a lot in value. But it’s also the most important!

While this is normal and expected, we are only humans after all and are prone to overreacting when noticing big drops.

To make it easier to avoid overreacting to changes in performance you should ideally pay as little attention as possible to how your investments are doing. That goes for both good times and bad.

In order to accomplish this, try to automate the acquisition of ETFs or index funds as much as possible.

- Set up an automatic bank transfer to your investment accounts.

- If your broker supports it, set up automatic buy orders for your chosen assets.

- Or if you have an assistant, family member or a good friend you can ask a favor, have them execute the trades for you every month (and have them not tell you anything about the state of your investments).

- If you must do the trades yourself, bookmark the order page and go straight there. Don’t peek at the performance of your portfolio. That’s only relevant when you retire (or to rebalance your investments).

In some countries you’ll also find automatic savings plans that deduct a set amount from your checking account every month, and places it into your chosen assets. While this may be a good option, be careful to check the fees closely. Your bank may also be executing market orders on an exchange with low trading volumes, meaning you leave money on the table for every purchase.

Go on a news diet

“The mental probabilistic map in one’s mind is so geared toward sensational that one would realize informational gains by dispensing with the news.”

— Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Just as you shouldn’t follow the day-to-day performance of your portfolio, also avoid paying any attention to financial news. If you read the financial or mainstream press at the time of writing (fall 2019) the media is saying the US economy is showing all sorts of signs of going into a slump, thanks in large parts to worse job numbers and Trump’s trade war with the EU and China.

Who would buy equities at such a time? You’d be a fool, no?

Well, if you had been following the news since the financial crisis more than a decade ago there has almost always been some elements of the economy making any cautious person nervous.

But if you had opted to not buy in—or to sell your holdings due to the pessimistic news reports—you would have missed out on what has been the longest bull run of the financial markets in history.

The news media make their money off your attention, and the easiest way to get your attention is to instill fear. In other words, they are incentivized to scare and shock you.

Consequently, the daily news contain mostly noise and very little signal. Your time is better spent doing pretty much anything else, such as picking up a book (recommended) or even binge watching the latest Netflix hit.

Buy regularly, ignore the news, and stay the fucking course.

Prefer limit orders

When placing your ETF orders with your broker, typically you will have to choose between at least two order types:

- Market order

- Limit order

A market order is pretty much what it sounds like: You buy at the current best price offered by seller—the current market price. This ensures that your order is filled quickly. However, you may be leaving a lot of money on the table (since you are accepting the current best offer), and the price might move unexpectedly between the time you place your order and when it is processed by your broker.

On the other hand, with a limit order you decide which price you are willing to accept, and the trade will only be executed if you get the specified price or better. This can save you a significant chunk of money, especially in the case of low trading volume, large bid/ask spreads, or highly volatile assets.

There are at least three ways you can use limit orders to your advantage when buying an ETF:

- More effort, slower execution speed, potentially lower price: Look at the recent price graph of the ETF to spot how much the price tends to fluctuate. Then set your limit order close to the bottom of that short-term range. Your order may take some time to fill, if it fills at all. If it doesn’t fill, you’ll have to cancel the order and place a new one closer to the current price. I would personally only use this method for large orders where there’s a lot of short-term volatility.

- Balance between price and execution speed: Place your limit order at or close to the current bid price. It’s likely that your order will be filled relatively quickly, and this way you’re not “giving away the spread” (as you would in a market order). This is what I normally do.

- Priority on execution speed: If you are willing to give away the spread (like with a market order), but want to protect yourself from sudden adverse price movements, you can place what’s called a marketable limit order. This means that you’ll place your limit order at or slightly above the current ask price. Unless the market moved quickly away (what you are protecting yourself from), your order should be filled nearly instantaneously. I personally do this if I am making a small order, the bid/ask spread is insignificant, and I don’t want to wait around for too long to make sure my order gets filled.

When placing limit orders you may encounter a question of whether you want to make a GTC or a regular day order.

A day order is good until the end of the trading day—if your order wasn’t filled by the time the exchange closes, it is cancelled automatically. If you still want to make the trade, you have to submit a new order.

On the other hand, a GTC order (Good ‘til cancelled) will remain active until—you guessed it—it is cancelled. Note that many brokers will cancel a GTC order after a set amount of time (often 30-90 days) to protect investors from long-forgotten orders executing when no longer desired.

If placing GTC orders, I recommend checking back in within a day or two to see if it filled, and—if it didn’t—modify the order accordingly.

Rebalance your portfolio

In order to adhere to your chosen risk profile (plus help you buy low and sell high), you need to maintain the appropriate split between equities and fixed income in your portfolio. You achieve this by rebalancing regularly.

Rebalancing just means that when your investment starts to deviate from your chosen allocation, you make the necessary trades to get your holdings back to your preferred split.

For example, let’s say you have decided on a 80/20 split in favor of equities and have a total of $10,000 invested. At this point you have $8,000 in equities and $2,000 in fixed-income investments. But say that equities then outperform your fixed-income investments for some time, you may end up with $10,000 in equities and still $2,000 in fixed income assets.

At this point, you can either:

- Sell $400 worth of equities and invest it in fixed income assets. You’ll have $9,600 and $2,400 respectively, or a 80/20 split.

- Don’t sell any equities, but rather invest another $500 into fixed income, leaving you with $10,000 and $2,500 respectively, which is also 80/20.

If you prefer the first option, I’d recommend picking a day (e.g. your birthday or January 1) and doing the rebalancing on that day every year. Put it in your calendar and stick to it.

There are however two problems with option 1: Potentially increased transaction costs and triggering a taxable event.

If your trading costs aren’t zero, then you could save money on rebalancing with your trades (option 2).

Depending on where you live and the type of investment account you’re using, you may trigger capital gains tax when selling some of the best performing asset class.

Both of these problems can be avoided by rebalancing with your regular trades instead, which is why I generally prefer that myself.

To rebalance with your trades, I’d recommend using this calculator for figuring out how much you should invest in each of your assets every month. But keep in mind that if you pay per trade, you may be better off only investing in one asset per month (the one that needs the largest contribution) even though the calculator recommends two or more trades.

If your investments are sufficiently large compared to the amount you’re putting in or taking out every month, then rebalancing with your trades might not be enough if the market moves very quickly. At that point you still may have to resort to option 1 to get back to your preferred split.

In that case, you can use this calculator instead.

Build ladders

If you are investing in individual bonds or utilizing CDs or term deposits for the fixed income portion of your portfolio, you should consider building ladders.

A ladder can be useful when you want to maximize your returns but still want to retain some access to the capital at regular intervals.

Say you want to invest $10,000 into CDs, instead of investing it all into a 5 year CD to maximize the interest rate, or into a 1 year CD to make sure you can access it all in just 12 months, you can invest $2,000 in a 1-year CD, $2,000 in a 2-year CD, and so on until you have one CD maturing each year for the next 5 years.

This way you take advantage of higher rates, but can still access and reinvest (e.g. to rebalance) parts of your investment every year.

If you don’t have an immediate need for your whole investment after the 5 years (e.g. if you have a big planned expense), then you can keep the ladder going by reinvesting what you got back after the first year into a new 5-year CD. Keep this going and you’ll now have a rolling ladder where you eventually have one 5-year CD maturing each year, maximizing your returns and still allowing access to capital yearly for reinvestment and rebalancing.

A rolling bond ladder performs very similarly to a bond fund with a fixed maturity, and in many cases you’d be better off just buying the bond fund instead of dealing with your own ladder. One advantage of the bond fund is that you can sell it at any time if you ever need access to the principal.

You can read more about when it makes sense to use a rolling ladder or a bond fund on the Bogleheads Wiki.

Build an emergency fund

While it may seem obvious to many, I still want to mention the importance of having an emergency fund of about 3 months living expenses.

This way you won’t have to liquidate any investments or rely on credit cards if you suddenly have a financial emergency on your hands. The former may trigger capital gains taxes or locking in a loss, while the latter could cause high interest payments and a lower credit score—making it harder and more expensive to get credit in the future.

Your emergency fund should be accessible on short notice, so it’s best to use high-interest savings accounts or no penalty CDs for storing the funds.

Optimize and pay taxes (if due)